Adrian Turner and the Everyman staff in the 1970s

Posted January 2022

Adrian Turner worked at the Everyman from 1971 to 1977, initially as Assistant Manager and, after the death of James Fairfax Jones in 1973 as Programmer. A full account of his time at the Everyman can be found in Guest Blogs.

The Everyman itself was a bare bones cinema. No frills or fluff, none of the opulence or flights of fantasy that many sought in cinemas. It wasn’t a flea-pit of the sort seen in The Smallest Show on Earth though aspects of that classic little comedy were real enough at the Everyman. There were never advertisements, trailers, let alone a kiosk selling Butterkist and Kia-Ora. The seats were hard and the screen did not benefit from the luxury of curtains, just a green footlight. The roof was wooden and vaulted, what you might call budget hammerbeam. The toilets, especially the gents in the basement, were fairly basic. In the foyer was a small commercially run art gallery, curated by Mrs F-J. The interval music was chosen by manager Dennis, always classical and meticulously transferred to tape from his LP collection. It was all . . . so very Hampstead.

Being a cinema manager wasn’t an especially onerous task, although there was I suppose an overall responsibility for the safety of a potential 302 paying customers and staff if, say, a fire broke out or if someone had a heart attack which, fortunately, no one ever did. However, there was the occasional momentary loss of bodily self-control which meant a rapid cleansing of the ablutionary facilities. That was what real cinema management was all about, not choosing this Godard over that Visconti but mopping up after someone’s stinking mess.

Dennis Lloyd had been the manager for many years and he showed me the ropes. On my first day he took me through the opening and closing procedures, a routine of chains and padlocks and, in winter, attending to the incredible vintage gas heaters which hung from the walls of the auditorium. When those heaters were on you could hear the gas hissing and see the pilot flames. They broke down frequently.

Dennis was in his mid-50s, a solitary figure, difficult to chat casually with. His private life was a closed book. He was always with a tweedy suit and tie, the corporal to F-J’s brigadier. Dennis lived in Wembley with his ailing mother and rode to the Everyman on an old motor-cycle. He resembled Richard Attenborough in Seance on a Wet Afternoon. Nevertheless, we got on extremely well. He realised I didn’t want his job, merely creative control of the cinema.

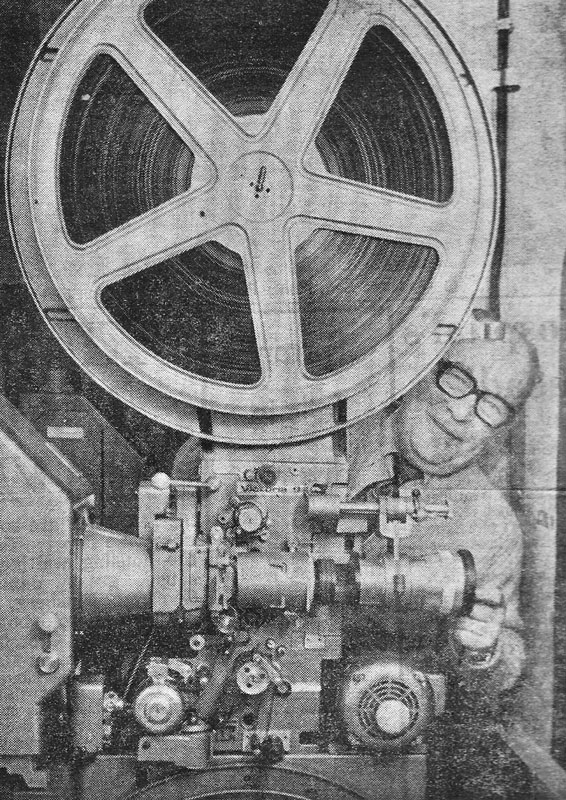

Upstairs was the projection box which was equipped with two Westrex 35mm projectors. These ran on carbon arcs which had their own distinctive sound and smell. On the wall between the projection box and the auditorium were several heavy fire shutters, needed because the Everyman was one of the very few cinemas in Britain licensed to show nitrate prints. One spark would set the whole place alight. A nice man came regularly to service the machines and I remember being madly impressed when he told me that another of his regulars was Stanley Kubrick’s home cinema.

Attached to the projection box was a fairly large sitting room for the projectionists’ sole use. It was filthy and stank of cigarette smoke, as did my office and Dennis’s domain which had the big wall safe and fireplace. Dennis smoked a pipe and I smoked unfiltered Chesterfields or Pall Malls. The whole place reeked of tobacco.

The chief projectionist was Tom Robinson, about 60, kind-hearted, slightly coarse. He had opened the Everyman with F-J on Boxing Day 1933 and had stayed loyal ever since. A family man, he lived in Edgware. He wasn’t really a film buff but he cared a lot about presentation. His assistant was Harry Walsh, of unknown age and a transvestite. One day he might be a man, another day a woman, whatever mood took him, though he wore high heels every day. He had a strong northern accent, waist-length grey hair and lived alone in a faraway world called South London. He looked desperately unhealthy, he chain-smoked and liked to shut himself away in the projection box and never see a soul. When he left the building I would watch people stand and stare at him as he walked over to the Tube station. But like Tom, I trusted him completely.

The box office boys and girls and usherettes were an extraordinary bunch. There were essentially two shifts. The afternoons were the domain of three elderly women. There was Birdie, full-blooded Irish, sassy and witty; there was Maud, a bit grim, skeletal, edging into dementia and heavily made-up; and Sally Bloomfield, the incredible Sally, almost totally deaf, with other medical issues, but so so kind. She lived down the road in what I always think of a typical Hampstead family – her parents were refugees, her mother fussing in the kitchen, her father a professor with more books in his house than the British Library.

Often in the cash desk was Mrs Heal, dressed in a shawl with dripping jewels. She was part-owner of Heals, the ultra trendy furniture store on Tottenham Court Road. Her daughter, with mane-like red hair, sometimes did a shift in the evenings, as did the gloriously Nordic-looking Anna who ended up marrying Martin Fairfax-Jones. In the evenings, the usherettes were mainly French and Italian students or au pairs. No one did this work for the money. They all liked the Everyman, they liked the company, the friendship, and they liked the movies it showed.

As the assistant manager I did a three-day shift, then a four-day shift. Dennis and I crossed paths on Wednesdays. Consequently, I had to deal with cash, usually not a great deal of it, and every night I had to pay the part-time staff and account for the box-office takings, put it in a bag, and drop it into the night safe at the bank across the road. I could have been mugged but this was Hampstead. The next morning I had to telephone Manor Lodge to advise them of the previous nights’ business. They were inured to disappointing news.

As a cinema manager you dealt with the public and in the Everyman’s case they were entirely pleasant and often up for a chat. In the eight years I was there I can only remember one awkward customer – a man named Michael Winner who demanded a free seat. David Lean (who came to see Top Hat) didn’t want a free seat, neither did John Gielgud, Kingsley Amis, Joan Bakewell, Peter O’Toole, cabinet ministers, or any other of the luminaries who came through the Everyman’s doors on a regular basis.

There was also, just the once, a Royal visit. On 1 March 1977 Frank Sinatra was playing the Royal Albert Hall. His friend Princess Margaret had tickets. Quite by chance we were having a season of MGM Musicals. On 28 February the phone rang and a voice said it was Kensington Palace. HRH Princess Margaret wanted to see High Society that afternoon and would be bringing her two young children with her. And at 2pm a Rolls-Royce arrived to disgorge the Royal party into our spartan picture house. To coin a phrase from Sir Tim Rice, I was at sixes and sevens and they were dressed up to the nines. Suit and tie for the young boy, an incredible mink coat for Margaret.

The local police station sent a constable to stand at the front entrance, a security man saw High Society with the Royal party and I had another security man with me in the upstairs office. He paid for their tickets. Before the film ended, he was on the phone organising all the traffic between Hampstead and Kensington, meaning there would be police at major junctions and traffic lights would be neutralised. If this sounds excessive, this was at the height of the IRA bombing campaign.

When the film ended, I was at the door, ready to discuss the subtleties of Charles Walters’s direction, the great performance of Mr Sinatra and the respective merits of High Society and The Philadelphia Story. But HRH just swished past me, a blur of fur, without even a look, though her two children shook my hand and thanked me for my hospitality. They had enjoyed the film, they said.

During my time there, two other things stand out. The change to decimalisation and the three-day week, when we all reverted back to the 18th century by living in candelight for much of the day. Like all cinemas, the Everyman was half on, half out.