‘At the back in the dark’: Pete Bell’s memories

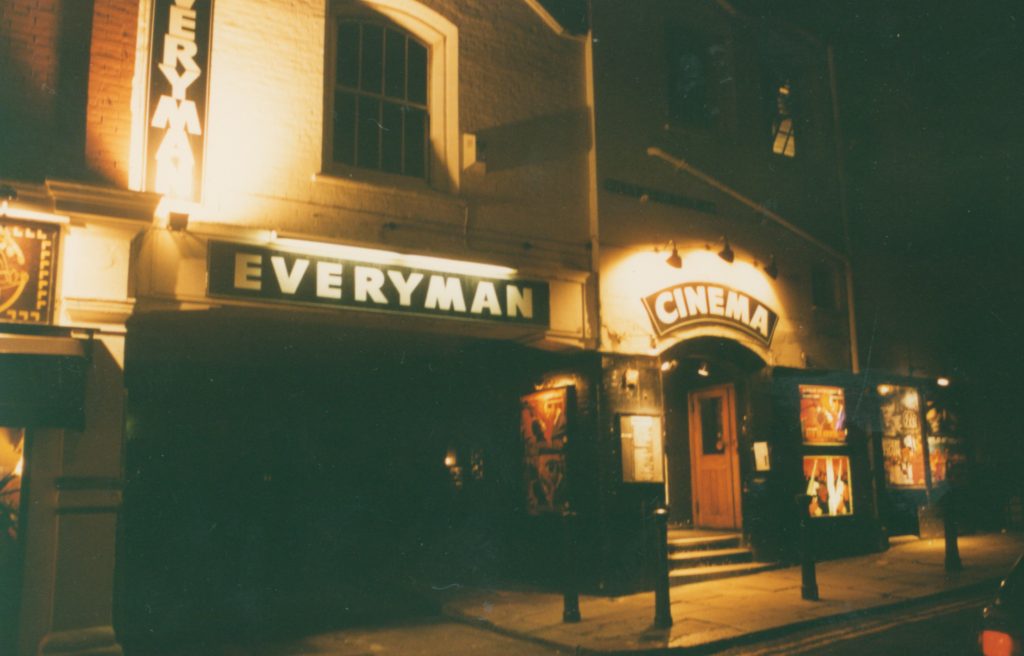

Pete Bell was a projectionist at three legendary arthouse cinemas; the Everyman, the Electric and the NFT (now BFI South Bank) where he still works part time and where, over coffee and croissants, he reminisced about his working life.

His career in projection started at the Electric in 1978. The iconic cinema on Portobello Road in the alternative neighbourhood of Notting Hill epitomised independent film culture of the 1970s – shabby, cheap and with an eclectic programme which ranged from arthouse to cult films. Whilst attending a film at the cinema he happened to notice a post-it note on the wall, advertising an opening for a trainee part time projectionist. He got the job and started training with the Swiss projectionist immediately. His home was only 100 yards away and his wife and son regularly brought in his meals on a tray, much to the amusement of his colleagues. The Electric was where he first got to know Peter Howden, later manager of the Everyman, who was the programmer there.

Around 1980 he applied for a fulltime job at the National Film Theatre where he stayed for most of the decade. Compared to the small single screen independent cinemas, like the Electric or Everyman, the NFT was generously staffed, with lead and second projectionists and reasonable pay and conditions. Pete had a drug problem which affected his time keeping but he also recalls that his colleagues, participants in the drinking culture of the 1980s, were sometimes not fully awake during their shifts. Nevertheless, it was an enjoyable place to work, and he remembers friends and colleagues from that time with affection.

He left the NFT in 1990 to go to a treatment centre and ‘get clean’. When he came back he needed something to do and approached Peter Howden who had joined the Everyman in 1981. Howden was a creative curator of film and his double and triple bills became legendary in the 1990s. He was ably assisted by Michael Brooke who has subsequently become a well-known film critic and writer.

In fact, this was not the first time that Pete applied to the Everyman. About ten years earlier he was interviewed by Martin Fairfax-Jones who had taken over from his father, Jim, who started the cinema in 1933. Pete was told to go and speak to the projectionist. In the projection room he met an unusual looking man with long ginger ringlets and wearing black tights. He was clearly using the projection area to sleep overnight. Pete sensed that his attitude was negative. One of the rectifiers/transformers started vibrating and groaning which the projectionist remedied by playing with a complicated set of switches. He rather grumpily indicated to Pete that he wouldn’t know how to do that. And Pete didn’t get taken on.

In 1990, however, Peter Howden jumped at the opportunity of offering Pete some part time work, standing in for Martin Percy who shared the projection with a French technician called Corinne. They did long shifts for half a week each. But Percy was an alcoholic and frequently off sick, so in time Pete took over as Corinne’s ‘other half’. There was also a resident cat called Xenor in the projection room which gave the place that distinctive smell. One of Pete’s tasks was to keep up the stocks of cat food.

The projection area was up two flights of stairs. The projection room itself was long and narrow. At one end was a rewind bench, then two 35mm Victoria 8 projectors and a 16mm projector next to the firedoor. This projector was carefully lined up to match the screen in the auditorium. Pete recalls an unfortunate incident when he found a 16mm projector on its side on the fire escape. Peter Howden had exchanged the Everyman projector with one from Riverside and had disastrously attempted to instal it himself. Behind that room was a larger room which held all that week’s films and those for the next week. In the days of triple bills and daily changeovers sometimes there were as many as 40 films stored there.

One of Pete’s abiding memories is of lugging the extremely heavy cans of films up and down the stairs. They arrived through the main entrance door on the street where the delivery drivers would unload them with the aid of a concertina hoist.

Peter Howden lived in a flat on the top floor with his own cats which had to be fed when he was away, much to the dismay of one assistant manager who reported that their claws were lethal. His office was on the second floor near the projection rooms. The floor had its own staff toilet which also housed cans of film squirreled away by Peter for the Everyman’s own unofficial archive. The Everyman held the only print of the 1965 Polish film The Saragossa Manuscript which had become a cult rarity. There were about 10 cans of film because it was over three hours long

Pete enjoyed working in Hamstead where he had his own favourite haunts including the legendary Louis the Hungarian patisserie, and the greengrocers opposite the cinema where he bought fruit and where he was popularly known as Mr Plum.

The cinema shared its side entrance with a local primary school, the Hampstead Parochial school. The kids went back and forth through the archway and much screaming and shouting could be heard from the playground. The cinema roof was full of their balls and had to cleared from time to time.

Summers were pleasant. The projectionists would stand out on the fire escape, their own private balcony, and watch the backroom ‘goings on’ behind the scenes at Daphnes, the Greek restaurant next door.

The Everyman was a good place to work despite the lack of a proper contract of employment. He was paid by the hour so there was no national insurance or sick pay. If Pete took a holiday he even had to find his own replacement. But he had a good relationship with Peter Howden who would often silently materialise at his shoulder in the projection box for a natter. Howden taught Pete the art of doing crosswords and they did the Evening Standard crossword together. Once, however, he blotted his copybook with his boss. Pete was rather fond of a young woman called Fenella who was the girlfriend of one of the ushers. One day, after she had broken her leg, he joined her on the floor of the box office area where she was resting with her crutch and her leg stretched out in plaster. It was not unusual to leave the projection room after changing the reel and he was enjoying keeping Fenella company. He was so absorbed in their conversation that he forgot about changing the next reel. Suddenly he heard the sound of the film at the end of reel and at the same time Peter’s footsteps on the stairs. He rushed into the projection box and saw the white light on the screen. He had to put the house lights up and change the reel which took three or four minutes. Then Peter Howden burst in and shouted ‘If I wanted to hire a c . . t I would have advertised for one’.

More than anything else Pete loved the atmosphere of the Everyman. Like all projectionists he often had to go into the auditorium to check the sound. But he also enjoyed watching the film there, standing at the back in the dark and joining in with the pleasures of watching a film together with audience. He particularly remembers doing this during the long run of Bertolluci’s 1900.

Because he worked half week on, half week off, he was there for long hours, from setting up before the matinee until the last film was rewound. By this time the cinema was deserted and all he had to do was let himself out the side door into the night. But this was precious time. He thought it was magic when the personality and history of the place re-asserted itself.