Bergman at The Everyman

By 1959 Ingmar Bergman had become the most popular arthouse director in London with no fewer

than ten films screening across the capital. The appeal of this remarkably prolific Swedish filmmaker,

whose international reputation was forged at the festivals of Cannes and Venice, rested on his

distinctive directorial style and the tackling of fundamental themes of love, death and religion. He

became the quintessential ‘auteur’, admired for his artistic independence and personal control over

the film making process from conception to final editing.

The West End first run art cinemas, especially the Academy in Oxford Street, encouraged the new

vogue for Bergman in the late 1950s and early 1960s with screenings which included The Seventh

Seal, Wild Strawberries, So Close to Life and The Virgin Spring. But it was the Everyman, with its

repertory screenings of revivals and its tradition of curating seasons, which became the regular

destination for Bergmanophiles who wanted to catch up with his films, both old and new, in order to

have the pleasure of appreciating his works as a whole.

In 1959 The Everyman put on a Bergman season consisting of four films Sawdust and Tinsel, Smiles

of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal and Frenzy. Thus began the long love affair between audiences

at the Everyman and Ingmar Bergman. These four films had been introduced to Londoners by the

Academy starting as early as 1946 with Alf Sjoberg’s Frenzy, written by the young Bergman. Sawdust

and Tinsel and Smiles of a Summer Night, shown in 1955 and 1956 respectively, did not make a huge

impact but The Seventh Seal which premiered at the Academy and ran for four months in 1958 was a

big hit. Set in the Middle Ages at a time of plague it tells the story of a knight who challenged Death

to a game of chess to save himself and his friends. Tackling the universal themes of sex, death and

religion the film also spoke to contemporary anxieties, with some reviewers, like Dilys Powell of the

Sunday Times, referring to the H Bomb. This film captured the imagination of English audiences and

set off a wave of enthusiasm labelled at the time as Bergmania.

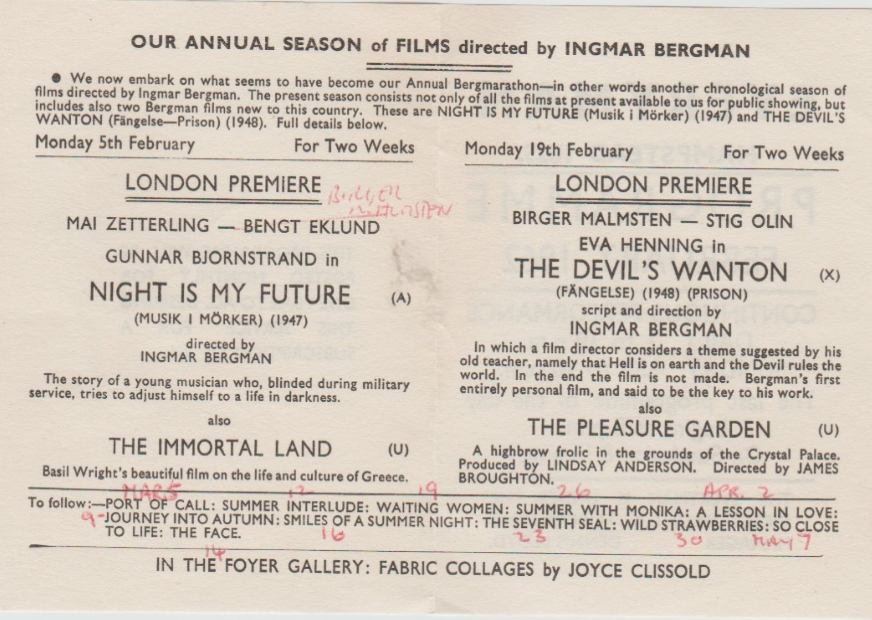

The Bergman seasons fast became a part of the cinema’s identity, with much bigger seasons of 12

films in 1960 and 1961. In February 1962 the programme proudly announced a new 13 film season

of all the Bergmans available in England starting with the London premieres of two early films, each

running for two weeks, Night is my Future made in 1947 and The Devil’s Wanton made in 1948.

These premieres were followed in March and April by Port of Call, Summer Interlude, Waiting

Women, Summer with Monika, A Lesson in Love, Journey into Autumn, Smiles of a Summer Night,

The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, So Close to Life and The Face.

Bergman’s films offered a sense of sexual freedom, already associated with continental, especially

Swedish, films. Many of his films were X certificated and even so, some were cut. However, at a time

when prudery and censorship still prevailed, foreign art films often managed to get away with

scenes of sex or violence that would not be tolerated in home produced mainstream films. Summer

with Monika, for example, made in 1953, concerned a girl who spends a Summer of love with her

young lover only to desert him once they are married. Played by nubile new star Harriet Anderson

the character in the film displayed the hitherto taboo casual looks and unconventional behaviour

which spoke directly to the new 1950s generation.

Bergman seasons continued in 1964 and 1967. Then, in 1971, when Fairfax-Jones was becoming ill,

he asked Adrian Turner, the manager/programmer if it was time to do Bergman again. Turner recalls

that the season he organised called Bergman Revisited was the biggest the Everyman had ever done.

Bergmania at the Everyman continued through the 1970s, culminating in a seventeen film season in

1977 which included more recent works like Cries and Whispers, The Magic Flute and Scenes from a

Marriage.

Bergman never went out of fashion at the Everyman. His new films of the late 1970s and 1980s like

Autumn Sonata and Fanny and Alexander appeared on the programme, whilst his older films

continued to be shown in the popular matinee double bills on a Sunday afternoon. For example, in

1983 and Summer with Monika with Smiles of a Summer Night. And Hour of the Wolf was paired

with Persona.

Before the coming of video, independent cinemas were the only source of films, both early and late,

of the great ‘auteur’ directors. The Everyman seasons and other screenings which offered a

’Bergman education’ were very well attended despite the fact that most of the prints were

apparently over-used and in a poor state. Nevertheless, all these years later, people recall their

experiences of Bergman at the Everyman with affection.