My Accidental Film Education and the Everyman Refugee Connection: Simon James

Posted May 2024

Simon James was brought up in Hampstead and read Philosophy at Sheffield University, where he helped the University cinema. He now lives near Swansea and has a passion for writing.

You could say that my education in film and world cinema started quite by accident. This is the story of that happy accident and how it intersects with a fascinating period of history in Hampstead which saw a large influx of mainly Jewish refugees arrive in London in waves in the 1930s.

My father Karl Rikowski was a refugee from Nazi oppression, who arrived in the UK in July 1939. After a spell of internment by the British government as an enemy alien, he was released in 1942 and settled in North London in 1943. Employment was sometimes difficult to obtain for a German national during the war, however Karl and some compatriot refugees started to build a niche offering in property renovation and maintenance. Their clients were mainly fellow refugees and displaced persons living in the Hampstead, Swiss Cottage and Finchley Road areas. It was around this time that my father met with Mr James Fairfax-Jones, the then owner of the Everyman Cinema. My father worked on and off for decades for Fairfax-Jones, maintaining the cinema and undertaking running repairs. Karl got to know the staff very well, and so it came to be that the Everyman became a sort of creche for my brother and I. Karl would drop us off at the cinema in the afternoon, and pick us up a few hours later. Of course we were not abandoned, rather we were under the watchful eyes of the staff in the Everyman, including the wonderful projectionist. And so our education in film started.

The programming in the 1960s included regular seasons of classics and trilogies mostly shown at the same time each year, sprinkled heavily with more modern releases. So there we sat in the high-backed seats of the Everyman and soaked up the Ealing Comedy season, including Kind Hearts and Coronets and The Ladykillers. Then the German expressionist season, Dial M for Murder, Nostferatu and Metropolis. Then The Satyajit Ray season. The Bergman season. The French New Wave season. Classics from Hollywood – Casablanca, Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon. The Andrzej Wajda trilogy starring Zbigniew Cybulski, the Polish James Dean. Films with wartime connections had a special resonance like The Third Man, which was a favourite of mine. Not to mention Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, and the Gorki Trilogy. And Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday by Jaques Tati. The list could go on and on. We saw the same films over and over again – which is no bad thing for such classics. As we watched and then re-watched films we noticed different things each time, especially as we started to get older and more mature.

In my adolescence and 20s my love of film continued, with many visits to the Everyman. This time it was often with a friend or girlfriend. And often we might see the old classics as well as new releases. It was always a wonderful and a very social occasion to catch up with friends one might meet in the queue, or meet over a glass of wine downstairs – perhaps enjoying one of the art exhibitions being shown by a local artist. There was always a good attendance by refugees, for example Mr Cohen who owned Hampstead Photographic in Heath Street, and also many well known people from the arts, including John Hurt, Ted Hughes, David Magarshack and Elias Canetti to name a few.

In the 1940s and 1950s the Everyman was an important institution for refugees from Germany and Austria fleeing persecution. Many refugees were attracted to the Hampstead and Swiss Cottage area, and notable refugees were members of the German Free League of Culture (a German, anti-Nazi, anti-Fascist, non-party, refugee organisation) based in 36a Upper Park Road, a leading member of which was the Stuttgart artist and writer Fred Uhlman. Meanwhile Austrians had their own cultural organisation – the Austrian Centre in 124 Westbourne Terrace, another hub of creativity and dissention, of which the poet and political activist Eric Fried was a member. My father told me that in the war many refugees would go to the Everyman not only to enjoy British and American films shown at that time, but also because it was warm and cheaper than feeding the gas meter in a bedsit or flat. After the war, when the international film programming recommenced the Everyman became incredibly important for refugees who could watch international films not shown in mainstream cinemas in London. It kept a cultural connection with European and world culture alive in a London that was grey, drab and still subject to rationing. And of course there was the vital social aspect and feeling of belonging it engendered. Refugee cinema goers would often meet up after the show for a coffee and post film critique in the Coffee Cup, the Cosmo in Finchley Road or the Prompt Corner in Pond Street.

In a way, back then the Everyman was a like a special club where you could celebrate film, culture and meet like minds and old friends. It was a cinema like no other and for me the relationship with the Everyman was a sort of love affair with the place, the people and the films I watched there. Thank you Mr Fairfax-Jones, I am indebted. I suspect many feel the same love for the place and are grateful that the cinema is now in new hands and thriving.

Copyright Simon James 2024

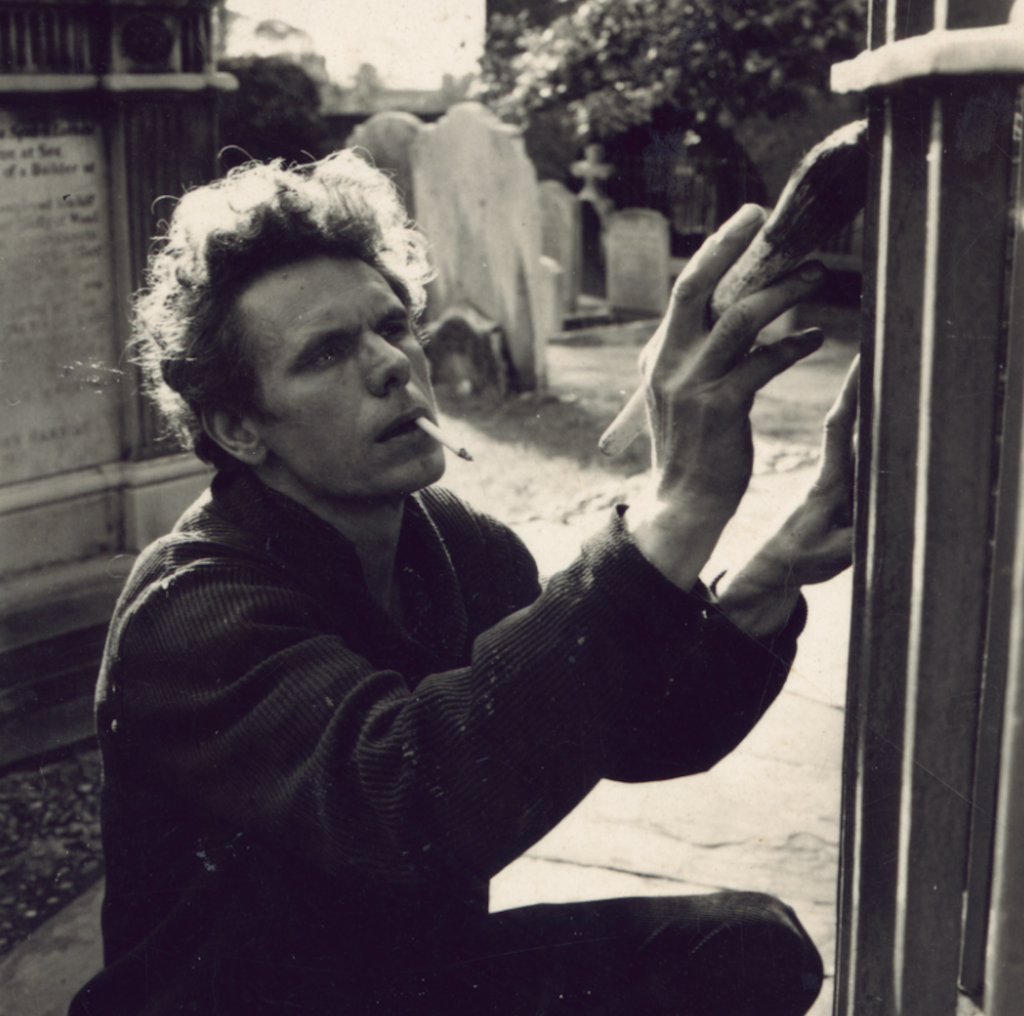

The author’s father, 1966, who maintained the Everyman, St Johns Church, Church Row