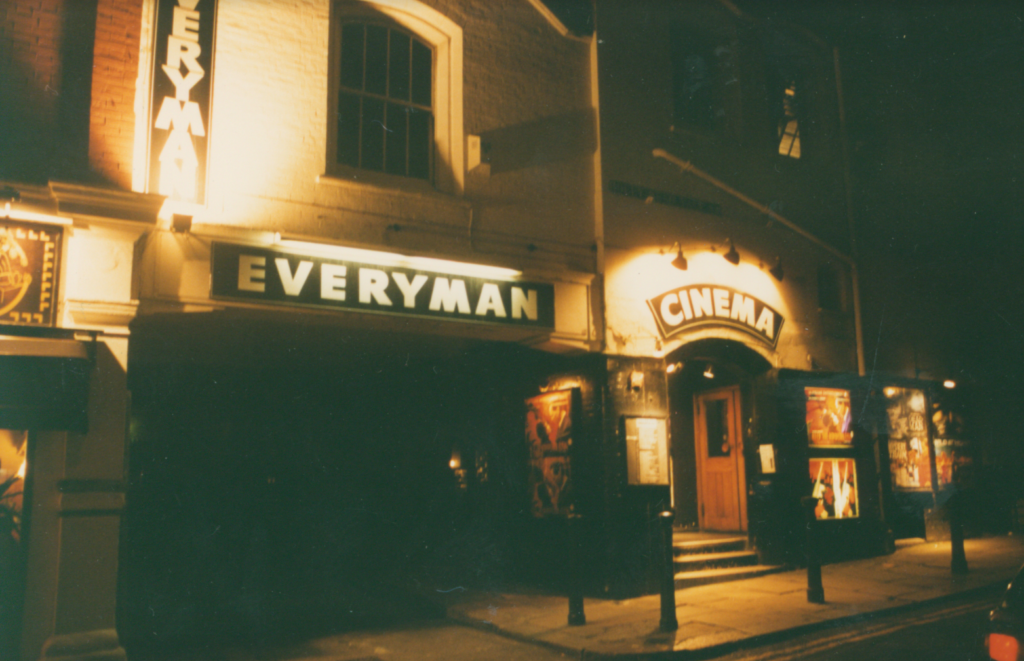

‘Something worthwhile’: Peter Howden at the Everyman in the 1980s and 1990s

Margaret O’Brien posted December 2021

This blog is based on a most enjoyable conversation with Peter Howden in the bar of the National Film Theatre (now called BFI South Bank), in November 2021. We talked about his time as manager and programmer of the Everyman, a position which lasted from 1981 to 1998. I first interviewed Peter at the Everyman in 1994, where he looked back on his previous programming role at the legendary Electric Cinema Notting Hill, in the heady days of the late 60s and the 70s, where he established a much-imitated style of repertory programming. After he left the Everyman his important role in independent cinema has continued, first as chief projectionist and then programmer at yet another landmark independent cinema, the Rio Dalston.

The Everyman in 1981 had a high reputation, based on decades of presenting the classics of world cinema. Established as a repertory cinema in 1933 by Jim Fairfax Jones, this single screen 300 seat arthouse had survived by showing revivals of the best of international cinema to a loyal local audience, as well as to cinephiles from all over London. When Fairfax Jones died in 1973 the Everyman continued as a family trust with his son Martin as managing director who employed various managers to organise the programming and day today running of the cinema. By the time Peter was appointed in 1981, however, audiences had declined, the cinema looked run down and the Everyman was now just one of a group of repertory cinemas in London, some of which had more adventurous programming.

Photo Bjorn Alnebo, Cinema Theatre Archive

Programming the Everyman

Despite these problems the cinema remained a major cultural attraction, not least for its pioneering seasons, ranging from the Marx Brothers to Bergman. Its location in ‘arty’ Hampstead right next to the tube was a further advantage, as was the support shown by local celebrities in the arts and media like Melvyn Bragg, Peter O’Toole and John Gielgud. Peter recalled one screening when both Faye Dunaway and Ken Livingstone were in the audience. The cinema, which received virtually no financial support, was let to the Everyman Trust by Camden Council for a peppercorn rent. There was one grant from the GLC (Greater London Council) in 1984 which was used to replace the seating, described by Peter as ‘falling to bits’.

On his arrival Peter made some radical improvements to the programming. He introduced frequent changes of film in any one week and expanded the number of screenings. Single screenings were minimised and double bills became the norm in the 1980s, followed by triple bills in the 1990s, all for the price of one ticket.

Unlike the Scala at Kings Cross and other rep cinemas which were programming cult genres like Italian Horror, Peter stuck to ‘the classics’, now including New Hollywood and British directors like Powell and Pressburger or David Lean, in addition to European auteurs. The Fairfax Jones tradition of showing the history of cinema, including animation and regular silent films was continued. Indeed, The Everyman still had its own small archive of films, including early animations like Joie de Vivre and the shorts of Richard Massingham

Quite a few of these historical films, like the WC Fields vintage titles which were not available on 35mm, were projected on 16mm. Pandora’s Box, a favourite from the silent era, was a 16mm stretched print with an added soundtrack. Buster Keaton silent films played well at sound speed and were often showed with live music. As it had been a theatre in the 1920s the Everyman acoustics were very good for silent films, much better than the Electric.

Peter took advantage of the release of new 35mm prints of arthouse classics like La Dolce Vita (which ran for four weeks), Le Mepris and Once Upon a Time in the West resurrected by the Electric.

His mission was to attract new, younger audience from across London. As always, the close proximity of the tube station was a distinct advantage. He programmed particular days of the week to appeal to different audiences. Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays were the busiest when lots of students came. Friday might be a little more ‘down market’, to appeal to a younger audience, Saturdays and Sundays saw new or recent releases, whilst the popular Sunday matinees were devoted to double or triple bills of classics, for example David Lean’s The Sound Barrier and Brief Encounter along with Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil were shownone Sunday in November 1983. On the other days of the week, there were usually extended themes or seasons like Film Noir or Godard. There was no pre-booking at the Everyman. On the other hand, tickets which were sold from different coloured rolls from a tin box, were cheap although you did have to buy Everyman club memberships, for 50p in the 80s. Ostensibly this was to avoid certification issues, but it was also a way of raising money

The reputation of the Everyman as a special place to go for London cineastes was enhanced by the publicity Peter was able to get from the leading listings magazine Time Out, with whom he had a longstanding relationship from his time at the Electric. The Time Out section on repertory cinemas was invaluable, especially when they picked out a special screening with a caption and photograph. The Everyman was also popular with the film critics, including Dilys Powell of the Sunday Times and Philip French of the Observer. When French was invited to the Everyman to speak about Film, a rarely seen silent short made in 1965, written by Samuel Beckett and starring Buster Keaton, he was so fascinated that he requested a second viewing. And this resulted in the lead review in his Sunday Observer article.

Running the Everyman

Picturesque Hampstead was a good place to run an independent cinema. It was a central part of a community which still held on to its artistic and bohemian identity There were also good local pubs and eateries including Daphne’s Greek restaurant next door where the staff celebrated Christmas every year and Louis the famous Hungarian patisserie.

The Everyman kept up its association with the visual arts, holding its own changing exhibitions of local artists in the foyer, curated since 1933 by Tess Fairfax Jones and advertised in the monthly programme.

Peter lived on the premises in what had been the caretaker’s flat which was reached by a staircase up from the manager’s office. He shared his living space with a succession of cats and mused that his cat Tinkerbell provided kittens for independent cinemas across London. His last cat Marmalade left with him in 2000.

One Christmas day, whilst at home in the Everyman, he heard the sound of breaking glass. The police arrived and the police dog searched around in the ladies in the foyer where they found a waterpipe had snapped under the weight of intruders. They must have panicked and run away.

He was very hands on – doing the accounts, seeing to leaking toilets and helping projection staff to lug the numerous and very heavy cans of 35mm films up and down the stairs. He had to keep up with technical developments and oversaw the installation of dolby stereo, the new four channel sound system. Fire regulations meant that, if someone was absent, he was sometimes obliged to take over as duty manager. Annual safety inspections sometimes resulted in inconvenient changes, for example he was once told to change the location a huge projector. The Everyman was a ‘No Smoking Cinema’ well before this became the norm: smoking was not allowed in the auditorium because of the flammable wooden ceiling.

The second half of the 1990s was dominated by financial problems for the cinema, exacerbated by unsuccessful investment in the café in the basement area. In 1998 Pullman Cinemas, a small chain, took over but heavy losses continued. Despite being offered a post by Pullman to programme both the Electric and Everyman, Peter left in 1998. Pullman suffered heavy losses and the cinema was purchased in 2000 by the Everyman Cinema Group. The Everyman Hampstead became the first of a successful chain of ‘lifestyle’ or ‘boutique’ cinemas.

When asked to review his twenty years at the Everyman Peter, with typical modesty, admitted he was proud that he managed to keep it going for so long and that he had achieved ‘something worthwhile’. Those who went to the Everyman in the 80s and 90s also remember that, in addition to its distinctive ambience, Peter’s cinema programme introduced or re-introduced them to a diverse and enjoyable range of cinematic experiences – a true film education.