The Everyman Cinema Hampstead in the 1930s

This blog has made copious use of a set of Everyman programmes which are on this website in the programmes section. Many thanks to Nick Davey who kindly scanned his precious collection to make these available.

The Everyman Cinema Theatre first opened its doors to the public on Boxing Day 1933 with René Clair’s Le Million supported by a Mack Sennett comedy, a Disney cartoon and Paramount news. The new cinema was to be run on a part time basis by solicitor James Fairfax- Jones (at centre of staff photo below) and his artist wife Tess who, on opening night were operating the cash desk and tearing tickets. The newly married couple had raised money from penny shares to take over a building described by Fairfax-Jones as ‘dilapidated, derelict and down-and-out’. Originally a drill hall built in the 1880s it was transformed in the 1920s into the famous Everyman Theatre which often put on controversial plays not shown in the West End. The theatre closed in November 1933 and the building was converted to a 285 seat cinema. In 1933 the odds were certainly against the new venture making a profit; Fairfax-Jones recalled that he was warned by a Wardour Street salesman that the project would only last six weeks. And, by their own admission, the couple were inexperienced in the business of running a cinema.

Like the handful of other specialist arthouses, the Everyman was set up as an independent cinema to show ‘good films’ from around the world. However, from the beginning, the Everyman was a repertory cinema showing revivals rather than first run films, with an emphasis on foreign language films. Fairfax-Jones envisioned the Everyman as a kind of film society with the general public as members. His experience of running the Southampton Film Society had inspired him to recognise the educational and democratic potential for film. He was also a member of the London Film Society where he was introduced to many films which were later screened at the Everyman. He did not approve, however, of the Film Society’s elitist and specialist image, nor the fact that the subscription was so expensive. He strongly believed that there could be a wider audience for international and avant-garde film.

The Everyman’s repertory programme had a weekly run starting, unusually, on a Monday. Showing revivals of ‘quality’ films in modest surroundings meant that tickets could be cheap, ranging from 2/- to 3/6d. The advertising which stressed the convenient location opposite the underground was aimed at a London wide audience through listings in such publications as the Times, Evening Standard and, from 1937, What’s On. But it was the Hampstead location which shaped the cinema’s identity from the start. Hampstead was known for its village atmosphere, its bohemian ambience and its reputation as a cheap place to live. The influx of artists, writers and architects from Fascist Europe in the 1930s added to the image of the historic village as a creative centre of the European arts.

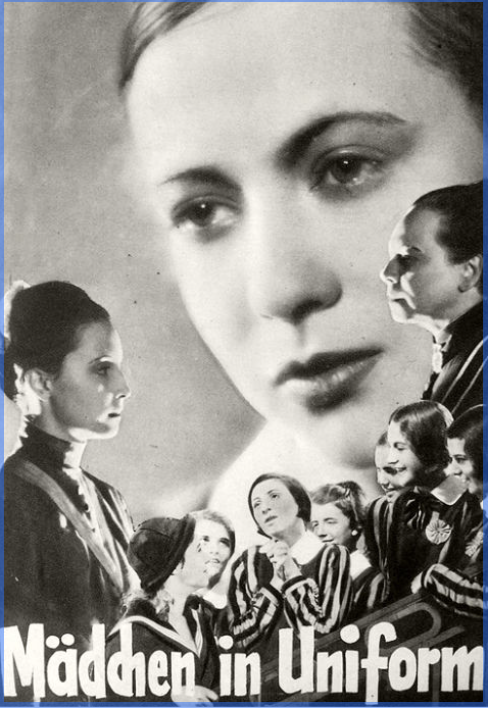

The early programming was to some extent experimental and showed an eclectic mix of feature films from Europe, the USA and Britain. From the start the supporting programme of shorts regularly offered a newsreel, a Disney animation (Silly Symphonies or increasingly Mickey Mouse), British documentaries and sometimes avant-garde art shorts. Before tensions with Hitler’s Germany became acute and German imports declined, the early features at the Everyman were mainly German, including repeat showings of favourites like The Blue Light, Mädchen in Uniform, Liebelei, M and The Blue Angel. The screening of Der Träumende Mund in March 1934 with Elizabeth Bergner, at the same time as her stage appearance in the West End, was highly successful. A Pabst season in 1935, which established the model for the famous Everyman director’s seasons, showed the much lauded Kameradschaft and the recent Don Quixote, as well as some of the early Pabst silent films.

French films in the early years included Poile de Carotte, La Maternelle, L’Ordonnance, Paris Méditerranée and the ever popular films of René Clair. A film, aptly named The Slump is Over, ran for two weeks in February 1935. A French musical with popular stars Danielle Darrieux and Albert Préjean, it was directed by Robert Siodmak. Following its premiere at the Curzon Mayfair it did so well at the Everyman that Fairfax-Jones dubbed it a turning point in the fortunes of the cinema which, he confessed, had been more than once near to closure.

The Russian Turksib and The Road to Life, an early sound Soviet export, both billed as masterpieces, were shown in 1934 and repeated in the following year. Turksib, an early experimental documentarybecame a favourite throughout the 1930s. In 1938 there was a whole season of Russian films which included The New Gulliver (1935), an early feature length stop motion animation with a strong anti-capitalist message. It was shown with Spanish Earth, Joris Ivens’ pro Republican documentary, the double bill no doubt an indication of the political leanings of both the owners and the audiences of the Everyman.

‘Quality’ American comedies, often based on stage plays, were also included in the programme from the early days, starting in 1934 with two Cukor films A Bill of Divorcement and The Royal Family of Broadway. Audiences flocked to The Guardsman in May 1934, a film version ofthe stage comedy with husband and wife double act, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontaine, who fortuitously were enjoying a big success on the London stage at the time. The film was shown twice as were the comedies of German emigré director, Ernst Lubitcsh whose Trouble in Paradise and Desire starring Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich proved popular.

Everyman Seasons and Events

Gaumont British seasons of home-produced films became an annual fixture during the holiday periods. In 1937 there was short Hitchcock season at Easter, followed by a longer Gaumont British season in August which included Things to Come, Rembrandt and Sanders of the River, revivals of popular circuit hits.

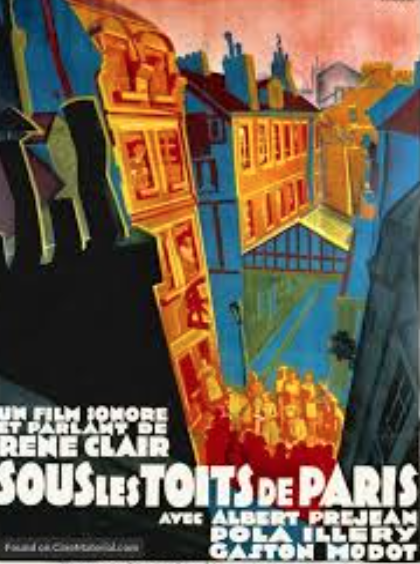

This grouping together of films into seasons, not just of national cinemas as above, but of directors and performers, became a distinctive characteristic of the Everyman programming. At a time when the idea of the director as the sole author of a film was not yet widespread, the directors’ seasons can be seen as particularly innovative. The most popular director at the Everyman was René Clair whose films like Sous les toits de Paris, Le Million, A nous la liberté and Quatorze Juillet occupied a special place in British film culture. With their allure of cinematic ‘Frenchness’, so attractive to some British audiences, Clair films actually got national distribution. Enlarged Clair seasons, including revivals of his earlier silents, like An Italian Straw Hat, continued to run every year at the Everyman until war broke out and for years after that.

The foreign language films chosen for the Everyman were often promoted on the strength of their star appeal. French stars in particular, were popular. After her appearance in Clair’s Le Million and Quatorze Juillet Annabella’s star appeal was always highlighted in Everyman publicity. French male stars were popular too, for example Raimu in Carnet du Bal, Charlemagne and The Strange Mr Victor, Louis Jouvet in Mister Flow, Entre des Artistes and Education de Prince; and Jean Gabin in La Bandera and Underworld.

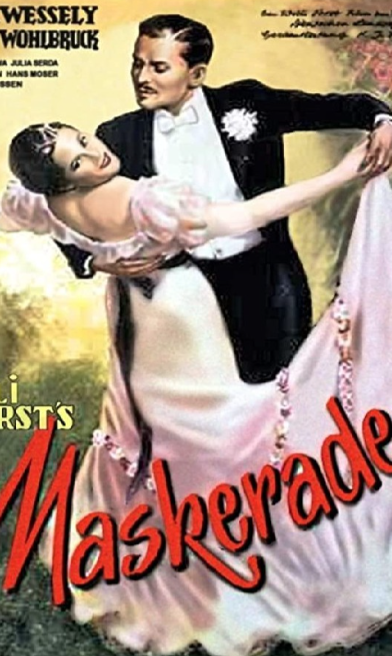

But it was the Austrian stage actress turned film star, Paula Wessely, who most impressed the Everyman audiences. Her first film at the Everyman was Maskerade, one of the ‘Vienna films’, a genre which became popular in Britain in the 1930s. With its expressive use of music, Viennese historical setting and elaborate costumes and mise en scène, Maskerade was released in over a thousand cinemas. It was not shown at the Everyman until November 1935 but in the meantime So Ended a Great Love, another Wesseley costume drama directed by Willi Forst, ran for two weeks in June of that year. In 1937 a Wesseley season, revived these two films and introduced Episode which was so well attended that it ran for a second week.

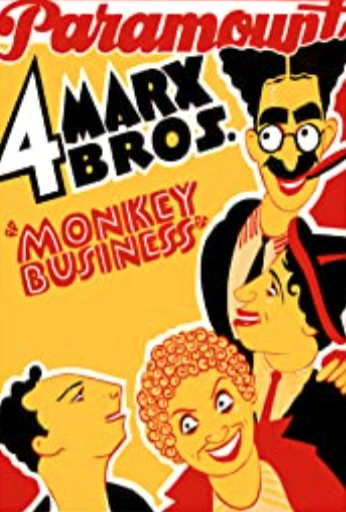

The Marx Brothers’ comedies became great favourites. The first season of Monkey Business, Duck Soup, Animal Crackers and The Cocoanuts opened in January 1936, and repeat seasons were put on in 1937, 1938 and 1939. For many Londoners the Marx Brothers and the Everyman were inextricably linked and they remained a staple of the Everyman programme for decades to come.

In May 1936 the Everyman put on a pioneering season, A History of the Film, which helped to promote a shared history of, and status for, the newly established art of film. The season re-visited the birth of film with the Lumières and other examples of very early films including The Great Train Robbery, as well as a full length screening of D.W. Griffith’s three hour spectacle, The Birth of a Nation. The stars of the silent cinema, including Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Marie Dressler and Rudolph Valentino were resurrected for this season. French, Russian and British documentaries were shown, as well as sequences from the first talkies. Landmark feature films were chosen including All Quiet on the Western Front, The Front Page and the sound version of Blackmail. The season culminated with Bonne Chance the romantic comedy and latest success of writer, director and star of stage and screen, Sacha Guitry.

The cultural event which attracted most critical attention in the 1930s was the first ever Surrealist film programme in 1937. The Everyman put on a press show and gala screening of Jean Vigo’s Zero de Conduite, the young director’s anarchist-leaning film about schoolboy rebellion. Banned in France and then refused a certificate from the British censor, it required a special London County Council certificate for its world premiere at the Everyman. The film, accompanied by an impressive array of surrealist shorts by Len Lye and Oscar Fischinger amongst others, created a sensation, and ran for five weeks.

Engaging with audiences

From the beginning The Everyman became, unusually for a cinema at that time, a centre for the display of contemporary art with foyer exhibitions curated by Tess Fairfax-Jones. Sometimes connected to the film programme and always advertised in the postcard programmes, the foyer exhibitions were an integral part of the cinema’s activities and the Sunday morning exhibition openings were part of Hampstead’s lively art scene. Tess, a practicing silversmith, showed a wide selection of artists many of them, like William Scott and Paul Klee, being introduced to London for the first time. Other exhibitors who became well known included the Mall Studio group of Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, and also Paul Nash, John Piper, Mary Kessel, Edith Tudor Hart and Anthony Gross.

Again, unusually for a cinema, but true to its educational mission, the Everyman had its own film societies, including a children’s film club set up in 1934 (see ‘Good films and good fun’: children at the Everyman in the 1930s in My Blogs) The Everyman Film Society for adults, also set up in 1934, met monthly on a Sunday afternoon in the large basement area of the cinema. Its stated aims were to show films which did not have a certificate from the censor, to revive films of interest, both sound and silent, and to promote experimental films. Discussion was an essential part of each session and the aim was to have a guest speaker, usually a film maker.

By the late 1930s the Everyman had built up a loyal audience. Fairfax-Jones reported that the cinema had a large mailing list, reaching four figures within a couple of years of opening and which was 7,000 strong by 1937. The programmes section on this websiite has many examples of the free monthly postcards which listed times, titles, seasons and stars as well as regular requests for feedback from the audience on the choice of films and suggestions for other films.

Evidence of the involvement of the Everyman audiences was provided by a plebiscite (people’s vote) in 1937. Patrons were asked to select, from a list of films, six they would like to see again. An impressive total of 1,000 replied: the most votes went to Mädchen in Uniform, followed by Kameradschaft, Maskerade, the original version of Unfinished Symphony, Turksib, Trouble in Paradise and The Petrified Forest. The re-screenings of these films in June and July 1937 then resulted in record business for seven consecutive weeks.

Popular British films with a family appeal were not forgotten, however. The comedies of the famous music hall duo Jack Hulbert and Cicely Courtneidge were shown plus the occasional popular hit like Sunshine Susie or Deanna Durbin in Three Smart Girls. These became regular features of holiday periods, as did the films of Alfred Hitchcock. British films enabled Fairfax Jones to fulfil the 20% quota of British films imposed by law at the time. In contrast to the West End specialist art cinemas, the Everyman, over the course of the year, offered a broad programme which included revivals of the best popular films from the circuit programmes. The holiday programme was another example of the inclusive programming strategy developed by Fairfax-Jones, a strategy still adopted by independent cinemas today.

For a more detailed account of the Everyman in the 1930s see The Everyman Cinema Hampstead: film, art and community in the 1930s, Margaret O’Brien, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol 41, 2021 – Issue 4.