The Everyman in World War II

Special thanks to Oliver Hylton for the extracts from the wartime logbook

Britain’s declaration of war in September 1939 caused the temporary closure of all cinemas for two weeks. The Everyman re-opened on Monday 25 September with the British-produced film Stolen Life (1939) followed by a series of French films including Hotel du Nord (1938), Le Roman d’un Tricheur (1936) and Knight without Armour (1937). The Everyman’s capacious basement was converted into an ARP (air raid precaution) shelter which the monthly postcard programme described as located ‘in the bowels of the earth far beneath. No cinema for miles around can offer these facilities. The auditorium can hold the entire audience. We shall do our best to entertain you with a catholic selection of the best films available, we need your patronage’. Sadly, the cinema was forced to close in September 1940. Blackouts and bombs had become part of daily life in Hampstead, despite the fact that the area was of no military significance. The War had also put a stop to the import of continental films, a mainstay of the Everyman’s programme in the 1930s. Meanwhile James Fairfax-Jones, who had run the Everyman since late 1933, whilst also practicing as a solicitor, was called up for service in the legal department of the RAF headquarters in London.

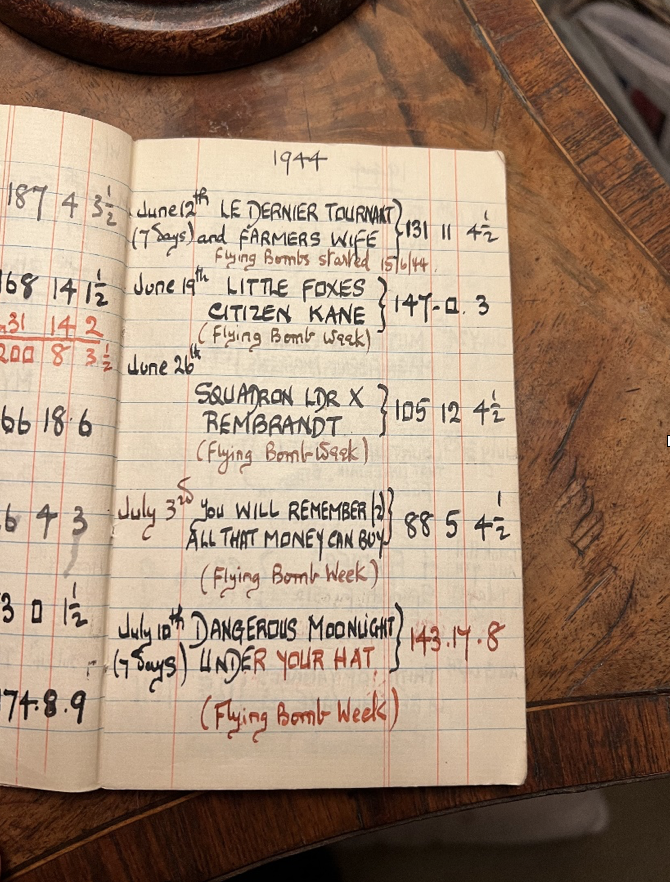

The cinema remained closed until June 1943 when it was sublet by Fairfax-Jones to Vincent Beecham, an experienced cinema operator, who was to run the Everyman till early 1946. Beecham followed the usual pattern of a twice weekly change of double bills on a Thursday. The first screening on 25 June 1943 was Smilin’ Through (1941) an MGM technicolor musical. From Thursday the main feature was the highly popular Victoria the Great (1937) with Anna Neagle and Anton Walbrook which was paired with a British comedy OK for Sound (1937) featuring the Crazy Gang. This mix of mainly British and American revivals (with the occasional foreign language film like La Bête Humaine) continued throughout Beecham’s time at the Everyman. Mostly they were films from the 1930s, ranging from Hollywood classics like A Star is Born (1937) or Grapes of Wrath (1939) to British thrillers such as Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938). Historical dramas including Catherine the Great (1934) and The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934) and adaptations of novels such as The Mill on the Floss and South Riding were also programmed.

Not surprisingly war films joined these popular genres on the Everyman screen. Two Hollywood films shown at the Everyman in 1945 are interesting examples of how the War was represented. Song of Russia (1944) a romance set in wartime Soviet Union between an American conductor and a beautiful Russian pianist is now remembered as a rare example of a mainstream pro-Soviet film. Lifeboat (1944), directed by Alfred Hitchcock, about survivors of a Nazi U-boat attack who discover that the German captain of the torpedo ship is also in the lifeboat. The film was criticised in the USA for being not being sufficiently anti-German.

British war films, included Tomorrow we Live (1943), an espionage drama made in co-operation with De Gaulle’s French National Committee. Set in a small town in German occupied France it deals with German atrocities and French Resistance. San Demetrio London (1943) from Ealing Studios a docudrama about the daring salvage of an oil tanker hit by enemy fire in the Atlantic was an Ealing Studios realist version of a true event.

A page from Beecham’s logbook of June and July 1944 below is an indication of the diversity of the Everyman programme which includes 30s classics, recent war films, a foreign language film as well as Citizen Kane which was to become the critics’ choice of best film and a staple at the Everyman in years to come.

This page of the logbook is also noteworthy because each weekly entry bears the words Flying Bomb Week. A total of 800 German long range rockets, nicknamed Doodlebugs, menaced London from mid-1944, causing higher casualties than the Blitz.

Seemingly audiences were not deterred by the dangers. Indeed, cinema going consistently remained the most popular entertainment during the War, with the Wartime Social Survey of cinema audiences in 1943 reporting that 70% of adults atttended regularly, with 32% going at least once a week.

Further evidence that the’ Everyman was popular with local audiences during the War and its immediate aftermath is provided by a letter from Mr G. Raymond of January 18th 1946. It refers to the screening of Pride and Prejudice, a lavish MGM production starring Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon. Mr Raymond stood in the queue with two friends for one hour and ten minutes in the cold evening of Tuesday 16th without getting in to see the film. He was however successful after queuing again on the following night. He wrote that he was cheered by the courtesy of the gentleman who came out from time to time to inform patrons of the situation. He was impressed by the ‘fairness, tact and common sense’ in the handling of such large numbers and he added that his good manners were commented on by everyone.

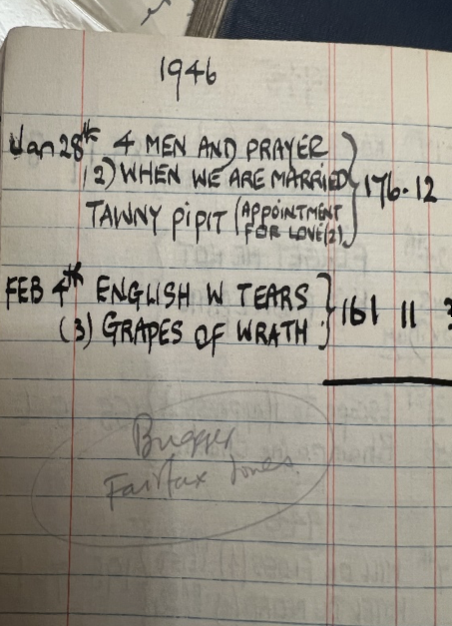

The War officially ended in September 1945. Shortly afterwards James Fairfax-Jones returned to civilian life and to running the Everyman. That Beecham was hugely disappointed is evidenced by an somewhat unconventional remark pencilled in the logbook below ‘Bugger Fairfax-Jones’. His last week of programming was 1 February 1946. Then the cinema was closed for a month and re-opened with Madchen in Uniform (1931) a popular favourite at the Everyman before the War.