The Everyman: the story of a building

Posted 28th April 2023

A walk through the Everyman today shows all the trademark features which have made the Everyman chain, with its emphasis on the hospitality and service side of film exhibition, so successful. The Hampstead Everyman now boasts two screens, one in the original main auditorium and one in the basement, each with capacious sofa seating with waiter service. There are several lounge bars and an extensive drinks and food menu. But, as this blog argues, this seemingly upmarket cinema continues to reveal its social and cultural past.

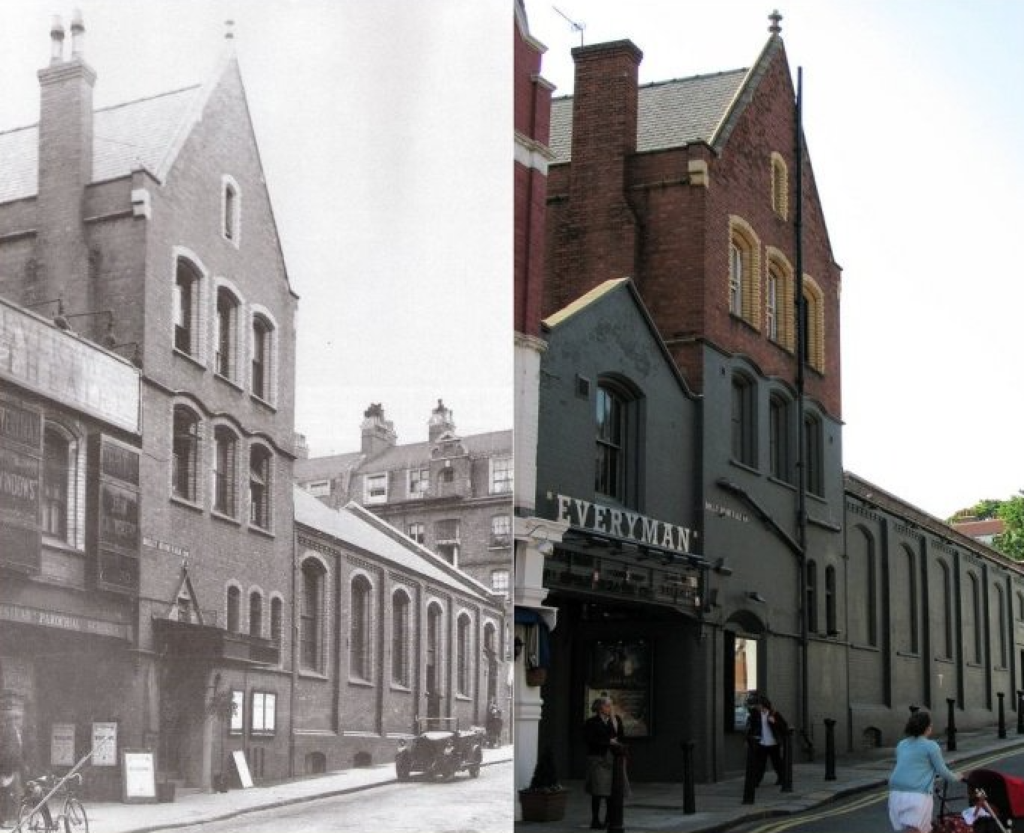

Drill Hall

The Hampstead Drill Hall and Assembly Room in Holly Bush Vale was built in 1888 for the local branch of the Middlesex Rifle Volunteers. Drill halls, which sprang up in the late 1800s in towns and cities across Britain, provided space for volunteer soldiers’ indoor drilling but were also, importantly, community centres for local people.

The main hall on the ground floor of the Hampstead hall had a vaulted ceiling made of wood and iron still largely untouched today. The large basement was used for entertainments including magic lantern shows. In 1899 it even became a venue for the new cinematograph shows. These events were accompanied by live piano music, as were the military drills. The building had a further two floors above the main hall, the first floor was probably for storage and administration whilst the top floor provided living accommodation for a caretaker.

The theatre

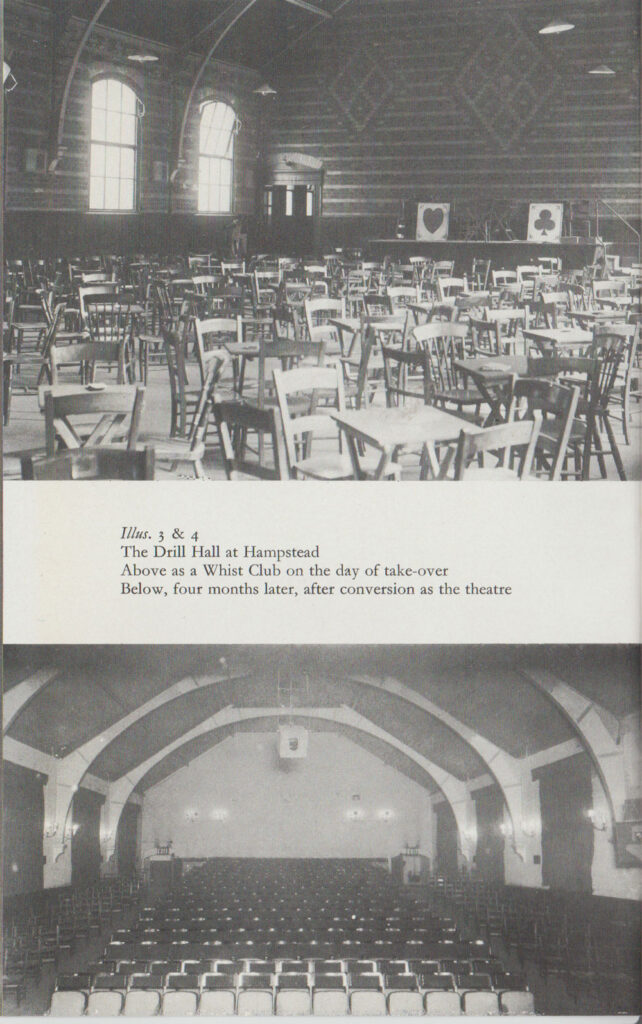

Shortly after the War when the hall had become a venue for public whist drives, the drill hall building was converted into a theatre, The Everyman, which opened in September 1920.

The Everyman Theatre was the brainchild of its first director, Norman MacDermott. Inspired by continental theatres and the ‘Little Theatre’ movement in the USA, he wished to stage more experimental work as opposed to what he described as ‘bedroom farce or leg show’ which predominated in the West End theatres. MacDermott put on the classics, such as Shakespeare and Molière and also introduced new plays by Eugene O’Neill, Noel Coward and George Bernard Shaw.

MacDermott’s description of the drill hall was less than complimentary. ‘It was repellent, bare brick, Victorian varnished wall lining, bare iron girders. It was being run as a shady Palais de Whist upon which the police had turned a jaundiced eye’.

Without the services of an architect or building firm the old drill hall was converted into an intimate 300 seat theatre with raked seating which allowed everyone in the audience to view the stage. The postwar shortage of building materials meant that MacDermott had to devise ways of turning ‘swords into ploughshares’. The existing army cook house was transformed into the proscenium arch, the remains of an aircraft hangar were used to create the steep rake in the auditorium where second hand cinema or church seats were installed. The usual footlights were abolished and were replaced by an imported lighting system from Germany. The existing windows were covered with heavy curtains.

The dressing rooms were located in the basement which meant that the only means of actors making an entrance on to the stage was by a narrow spiral iron stair case on either side at the back. The dressing rooms were divided by flimsy partitions which, according to one actor, gave the impression of horse boxes. An old kitchen range was retained in the basement and here the actors which included Edith Evans, Raymond Massey, Mrs Patrick Campbell, Ellen Terry and Claude Rains congregated for tea.

MacDermott left in 1926. He had achieved artistic but not commercial success. The theatre continued under different managements but by 1930 it was no longer commercially viable as a full time repertory theatre. In the early 1930s Consuelo de Reyes, a dramatist involved in community theatre, acquired the lease and used the Everyman for drama workshops.

Everyman Cinema 1933-1973

James Fairfax-Jones, a solicitor with a dream of opening a cinema, took over the building, which he described as ‘dilapidated, derelict and down and out’ on Boxing Day 1933. Alister Gladstone MacDonald, a successful architect whose work included news cinemas in London and other cinemas in Scotland, was employed to re-design the auditorium. The Everyman became a 285 seat cinema with the entrance directly on the street. The cinema was not successful at first but by the mid 1930s it had built a reputation which attracted London cinephiles as well as local audiences.

When war broke out the Everyman’s capacious basement was converted into an ARP (air raid precaution) shelter which the postcard programme promoted as an asset, creating a shelter ‘in the bowels of the earth far beneath. No cinema for miles around can offer these facilities. The auditorium can hold the entire audience.’ Sadly, the cinema was forced to close in September 1940. Blackouts and bombs had become part of daily life in Hampstead, despite the fact that the area was of no military significance. Fairfax-Jones was called up to a legal job in the RAF offices in London. The War had also put a stop to the import of continental films, a mainstay of the Everyman’s programme in the 1930s.

The cinema was sublet for a couple of years from 1943 but was eventually re-opened by Fairfax-Jones in February 1946. The programme resumed with old favourites from the 30s starting with Mӓdchen in Uniform but, like other venues in the immediate postwar period, the building itself looked distinctly neglected.

By the early 1950s imports of foreign films had resumed and there was even a thriving film club which met fortnightly on a Sunday afternoon in the basement. Here club members watched rare or specialist films on 16mm surrounded by old theatrical props and were fed homemade soup by the Fairfax-Jones family. In 1954 the cinema celebrated its 21st Anniversary with improvements to the

building, including new foyer exhibition space and the installation of the latest cinemascope equipment.

The cinema thrived in the late 1950s and 1960s. However, as an independent arthouse, it was not like other cinemas. Adrian Turner, who was programming manager from the late 1960s, describes its somewhat shabby appearance: it was ‘a barebones cinema. No frills or fluff, none of the opulence or flights of fantasy that many sought in cinemas . . . the seats were hard and the screen did not benefit from the luxury of curtains, just a green footlight. The roof was wooden and vaulted, what you might call budget hammerbeam. The toilets, especially the gents in the basement were fairly basic. The interval music was chosen by manager Denis, always classical and meticulously transferred to tape from his LP collection. It was all . . . so very Hampstead’.

Everyman cinema 1973-2000

Fairfax-Jones died in 1973. The cinema continued its repertory programming but like other repertory cinemas it was losing audiences and lacked the finances to invest in the building. It was saved by a package of financial support in 1984: £41,500 from the Greater London Council enabled a facelift for the cinema including the replacement of the notorious seats, a new screen and Dolby stereo sound system was installed thanks to Channel 4, and a much-needed new heating system was financed by the BFI and Camden Council.

A café was opened in the basement in 1986 and in 1991 it came under the direct management of the Everyman. The publicity made the most of the building’s historical associations, boasting the original French poster for Zéro de Conduite from 1937 as well as various theatrical props left over from the basement dressing rooms of the 1920s theatre. The café also briefly became a jazz venue until it was realised that the sound carried to the auditorium upstairs. Investment in the café was a further drain on the finances of the Everyman in the 1990s.

In 1998 when audiences had dwindled even further the Everyman was taken over by Pullman Cinemas, a small chain which already owned the Electric Cinema in Notting Hill. They employed Gebler Tooth Architects to redesign the Everyman into a ‘luxury space’. The entrance was moved from the street to the cul de sac at the side. The capacity in the auditorium was reduced from 287 to 196 to make way for the new sofa seating. The basement café and gallery were closed, and a bar area with adjoining bookshop were placed next to the box office. The total cost of this makeover was £800,000 but ticket income continued to plummet and Pullman put the cinema on the market in 1999.

Since 2000

In 2000 the cinema was bought by young property entrepreneur, Daniel Broch who took an unashamedly commercial approach to the cinema and its programme. A second screen was opened in 2004 in the basement. In 2007 a refurbishment updated the lounge, removed the bookshop and moved a bar into the space. In 2008 Broch resigned having turned the Everyman around and opened several other cinemas to form the Everyman Cinema Group. Today (2023) there are 38 Everymans nationwide and profits are going up, proof that the cinema going experience it offers appeals to a particular segment of the market.

But the building still shows the marks of its Victorian origins as a drill hall and its subsequent development as an experimental theatre followed by an arthouse cinema. Despite several refurbishments since 2000 the cinema with its side entrance, awkward stairs, dark nooks and crannies, and vaulted ceiling in the auditorium, still bears the traces of its varied social, cultural and artistic past.