Fairfax-Jones stories: an interview with Caroline Iliffe

Posted March 2022

I met Caroline Iliffe, oldest child of Everyman founders Jim and Tess Fairfax-Jones over coffee in her Camden Town home. Born in 1936 Caroline became an architect, as well as a wife and mother to three daughters. Still active and vibrant, she started an art degree in her seventies and graduated in silversmithing at the age of 75. She remembers her idyllic childhood and young adulthood in Hampstead and reflects on the importance of the Everyman for the family, the local community and London film culture.

Some wartime memories

Caroline’s parents, Tess and Jim married in St Jude’s in Hampstead Garden Suburb on December 23 1933, three days before they opened the doors of the Everyman for the first time. Neither was a Londoner. Jim’s family, from Bruton Somerset, later settled in Amersham. The family came to London from Southampton where Jim did his articles as a solicitor and where his early passion for film led him to set up the Southampton Film Society. Tess’s family lived in Kings Norton near Birmingham. From there she moved to London to attend the Central School of Arts and Crafts where she qualified as a silversmith.

By the time war broke out Caroline had twin siblings, Martin and Ruth, only one year old. Tess was able to evacuate with the three children to a beautiful thatched cottage, belonging to her sister, in the picturesque village of Welford-on-Avon. The cottage had no running water, no electricity and no heating apart from a wood fire. Nevertheless, Caroline remembers this as a happy time, with outdoor activities and frequent visits from Tess’s sisters. One childhood memory, however, is a vivid reminder of the privations of wartime Britain. Tess had a pen of chickens whose eggs were a precious commodity. After watching her mother make a cake, Caroline decided to follow suit and broke an egg into the sandpit, a terrible waste which caused Tess to burst into tears. During the latter years of the War Caroline saw her first ever film, Bambi, the Walt Disney film which was a big hit in British cinemas from 1943. She saw it with her cousin at the Rex High Wycombe, an independent cinema which her father co-managed for a period.

Back in London the Everyman had been forced to close in September 1940 due to blackouts, bombs and lack of films from continental Europe. Jim was called up to the RAF and was seconded to their legal department in London, although he did manage to visit the family on some weekends, travelling by train and bicycle. He remained in the family home, a big Victorian house in the Gables by the fairground in the Vale of Health. He shared with friends including members of the Massingham family. Richard Massingham was to become a lifelong friend. A doctor, film producer and director he also played the bumbling Englishman in many wartime instructional films, using humour to encourage citizens to save fuel or bath in no more than five inches of water.

After the War

In February 1946 Fairfax-Jones renewed the lease with Camden Council and took over the Everyman again. Caroline remembers the excitement surrounding this period when the Everyman’s programme returned and cinema queues often went round the block as far as John Barry the dress shop.

1946 also saw the resumption of the art exhibitions in the foyer, described by Caroline as ‘a funny little space’. The art exhibitions were started by Tess in 1934 and some of them including Paul Klee, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth attracted media attention. In the late forties and the fifties Caroline remembers that the children regularly helped with the hanging on a Saturday which was followed by a launch party and viewing on the Sunday morning. Tess was active in the Hampstead Arts Society, part of the local thriving art community, and was also involved in the Hampstead art fair which exhibited regularly in Heath Street. The exhibitions at the Everyman played an important role in the promotion of local artists for many years from 1934. From the 1980s Juliet, Caroline’s daughter, assisted Tess with exhibitions helped by Everyman staff, and then took over completely from 1991-94 after Tess’s death.

Jim and Tess’s family, now enlarged by the birth of Alice in 1946 moved to their new home, in the Vale of Health, Manor Lodge, in the late 1940s.

In the early fifties Caroline was taken by her aunt Phyllis on a ‘grand tour’ of Europe in a Triumph Herald. The trip lasted 28 days and she was given expenses of a pound a day by her aunt. She was invited on the trip partly to provide company to the daughter of her aunt’s friend and co-driver. Aunt Phyllis, a headteacher was an excellent tour guide. Caroline fell in love with Venice where they spent a week, and went back the following year with her parents and showed them around.. She also recalls seeing The Seven Samurai at the Venice Film Festival with them in 1954, an experience which deeply impressed her father and inspired him to show seasons of Japanese films at the Everyman. Jim and Tess continued to make an annual pilgrimage to Venice, taking in the Film Festival as well as the glorious gardens and palaces. Jim was commissioned by the Times to write reviews of the new films, some of which would eventually be programmed at the Everyman.

Caroline says that it was the Festival of Britain which aroused her interest in Architecture. As a young teenager she remembers cycling down to the South Bank at night and witnessing the Royal Festival Hall being built by floodlight. In 1954 aged 18 she entered the prestigious Architectural Association School. She was one of only seven girls out of a total intake of fifty for the five year training course. During this time she lived at home with the family in Manor Lodge. Her life was busy with her two main interests, Architecture and Music. She spent a lot of time studying, but in her time off Music was her main passion. She was more likely to be in a queue for a classical music concert at the Royal Festival Hall than going to a film at the Everyman.

She was, however, involved in helping her father recreate the scaling for ticket costs at the Everyman when he changed the pricing of the seats. Usually, the first two rows were reserved for students at the special price of one shilling. But when he screened a film of special interest to the youth audience the number of shilling seats was extended. She said that Jim was always concerned to make quality films from across the world accessible and cheap, and did target a London wide audience, although it was ’quite a trek’ to get to Hampstead on the northern line. The cinema announced its films across the London underground system on platforms and concourses with the distinctive black on yellow posters. Once in the queue filmgoers might be lucky enough to encounter Jim who, on most evenings checked on the popularity of his film choices. He also took a seat in the auditorium to check that sound levels were appropriate to the numbers in the audience.

Life at Manor Lodge

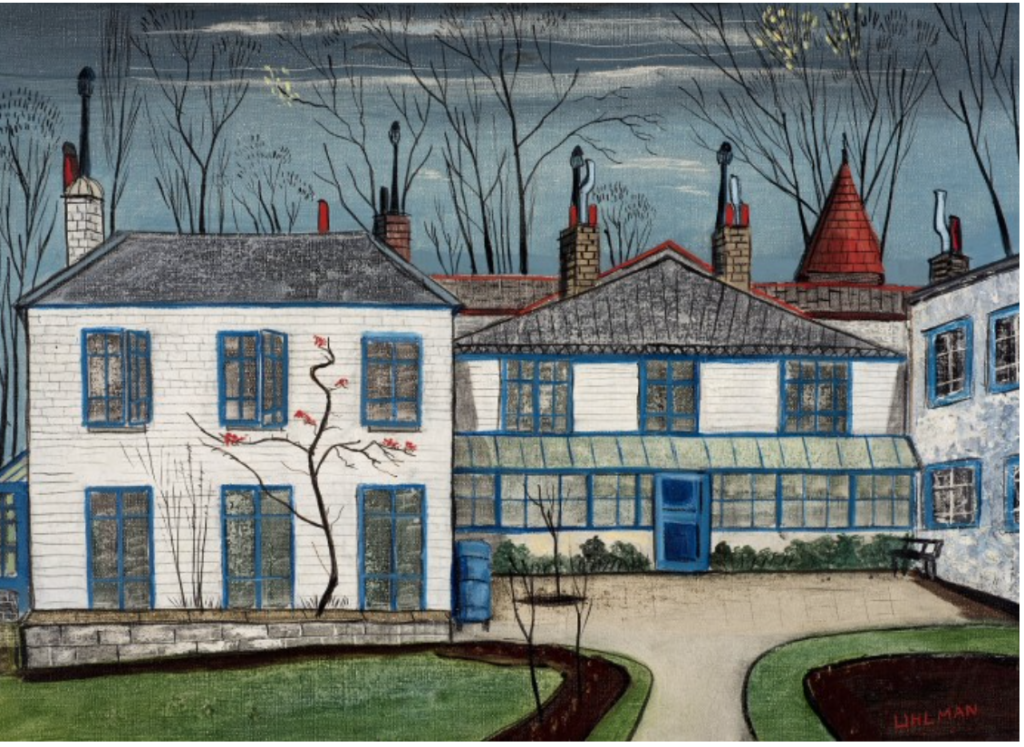

Caroline showed me a reproduction of a painting of Manor Lodge by artist and family friend, Fred Uhlman in 1952, currently in the Burgh House collection. It shows a pretty, early historic house, long and low and painted in blue and white. Tess and Jim lived there with their four children. Tess’s workshop and Jim’s legal offices were located in opposite wings. Manor Lodge was both spacious and picturesque, set in beautiful gardens. Caroline noted it was a lovely family home, where ‘we were so lucky to live’. It had two garages one of which housed Jim’s film collection including a number of rare flammable films. (The Everyman was one of the few cinemas which had a licence to show the early flammable films). It was an idyllic house with an exotic garden, nurtured by Jim. The location, Vale of Health a hamlet tucked away to the north of the Heath, was idyllic too. Her father loved it. With the exception of his trips to Venice he could not be enticed away for the family camping holidays. He stayed at home to work in his legal practice and his beloved Everyman, to tend his garden and walk on the Heath.

During the 1950s Caroline recalls that Manor Lodge was a social hub for artists and film people. Every year there was a garden party for all the Everyman staff. And the Fairfax- Joneses entertained many people from the world of film. Jim was friends with John Huntley of the BFI, Dilys Powell, film critic of the Sunday Times, documentary film makers Basil Wright and Paul Rotha and journalists from the Times and Telegraph. He also supported aspiring young film makers. Kevin Brownlow, then a teenage amateur film maker was allowed to shoot a scene of It Happened Here in the Manor Lodge garden. John Schlesinger, later to become a Hollywood icon, became a friend after Jim supported his first film, Black Legend, in 1948. Schlesinger was then a young Oxford student making an amateur film on a tiny budget.

When asked to describe her father Caroline said he was first and foremost a family man. He was actually quite shy and preferred to relate to individuals, unlike his wife who thrived in big crowds. The Everyman was his other passion, and he was always more interested in film than in his legal work. The Everyman probably just about broke even financially. But from its beginnings in 1933 until his death in 1973 it was always a true labour of love

Caroline’s final words sum up her admiration for her father: ‘He was an inspiration and support to me and my sisters and brother as we grew up and throughout our lives, giving us both emotional support and encouragement in all our aspirations. He was a caring and inclusive person who didn’t seek the limelight, he just wanted to share his great love of world cinema with others’.